BY ANGEL ADEBOWALE

CANDIDATES for the 2024/2025West African Examination Council (WAEC)has rejoiced over the results of their certificate examination, unaware that this might be one of the last time students their age would have the opportunity to sit for such exams, as a new Federal regulation loomed on the horizon, banning under-18 candidates from future certificate examinations, as they prepare to start their university journeys, they wander about the future of the upcoming secondary school students, caught in a shifting educational landscape.

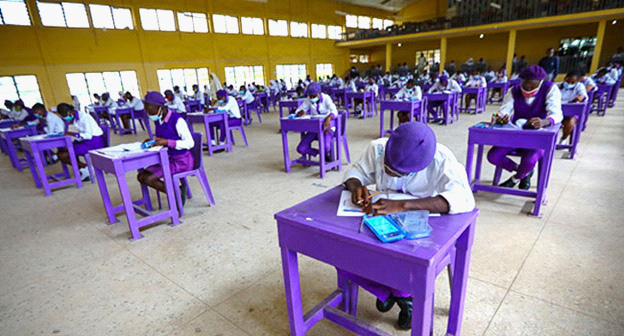

In Nigeria’s education system, students in their last year of secondary school partake in certificate examinations. The exams include West African Senior Secondary Certificate Exam (WASSCE), General Certificate Examination (GCE) and the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME).

The minimum number of subjects a candidate can sit for is eight whereas the maximum is nine. All Senior Secondary Schools in the Federation present candidates for the SSCE because the results are used for admissions into Tertiary institutions, employment purposes and qualification to stand for elective offices.

However, students who have been taking these examinations have an age average of 16 years. These students sit for these examinations at 16, and move on to the universities at that same age or a year older. This has been the situation for several years and the education system has adjusted to it.

However, the Federal Government has stated that the rationale behind the new rule is that the large number of under-age candidates sitting for the examinations are not qualified to be admitted into university. They also stated that if the educational policies that are already in place are enforced, then students will in fact not be under age at the time of enrolment into tertiary institution.

Recently the Federal Government declared that under-age candidates will no longer be permitted to sit for secondary school leaving certificate examinations (SSCE) administered by the West African Examinations Council (WAEC) and the National Examinations Council (NECO).

The Minister of Education, Prof. Tahir Mamman, disclosed this when he appeared on Channels Television’s ‘Sunday Politics’ programme on Sunday night.

The minister also stated that the age limit for candidates taking the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME), administered by the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB), remains set at 18 years. The minister also advised universities to refrain from issuing admissions to ‘unqualified children’.

This new policy was not received with open arms and has ignited widespread disagreement among both parents and students. This regulation is seen as a significant impediment to the country’s educational and professional ecosystem, which has long been one of its competitive advantages: the ability to produce young, fresh talent that is highly sought after in various industries. The implications of this policy are far-reaching and raise concerns about its potential to stifle the ambitions of Nigeria’s youth, disrupt the educational system, and diminish the country’s ability to maintain its edge in producing young graduates who can contribute meaningfully to the economy.

One of the primary concerns raised by parents and students alike is the issue of idleness. In Nigeria, the average age for completing secondary school is around 16 years. Traditionally, students who perform well in their exams have the opportunity to proceed directly to tertiary education, where they can further their studies and work towards becoming professionals in their chosen fields. However, with the new policy in place, students who complete secondary school before turning 18 will be forced to wait until they reach the eligible age to sit for their exams. This period of enforced inactivity is seen as not only unnecessary but also potentially harmful. During this idle time, students may lose their academic momentum, become disengaged from their studies, or even abandon their educational aspirations altogether. The waiting period could lead to a loss of interest in academics, with some students becoming discouraged by the delay in their educational progress. This enforced idleness may also contribute to negative behaviours, as students with too much free time and no structured activities might seek out distractions that are counterproductive to their long-term goals. Leading to petty crimes, prostitution or just general decadency.

Furthermore, this policy may have a detrimental impact on the Nigerian education system as a whole. The education system in Nigeria is already grappling with numerous challenges, including inadequate infrastructure, overcrowded classrooms, and frequent strikes in government-owned universities that often delay students’ academic journeys. The introduction of an age restriction on sitting for exams adds yet another layer of complexity to an already strained system. This policy disrupts the traditional progression from secondary school to tertiary education, leading to a backlog of students who are ready to advance but are held back by an arbitrary age limit. This disruption could result in a bottleneck effect, where students who are ready and eager to move forward are forced to wait, causing further delays and congestion within the education system. Over time, this could lead to overcrowded classrooms in secondary schools as younger students are unable to moveon to higher education, thereby compounding the existing problems of resource allocation and teacher availability.

The implications of this policy extend beyond the classroom and into the professional world. Industries in Nigeria and beyond have long recognized the value of young, dynamic talent, and many employers actively seek out fresh graduates who can bring new perspectives and innovative ideas to their organizations. However, by delaying students’ entry into tertiary education and subsequently into the job market, the policy could inadvertently reduce their employability. As students graduate at older ages, they may find themselves competing with younger candidates who have the advantage of youth, energy, and a longer career runway. This could diminish their chances of securing good jobs, particularly in industries that prioritize hiring younger talent. The delay in completing their education could also mean that Nigerian graduates may enter the job market at a time when their global counterparts have already gained years of experience, putting them at a disadvantage in the increasingly competitive global economy. Moreover, as technology continues to evolve rapidly, the knowledge and skills acquired in school might become outdated more quickly, leaving delayed graduates less prepared to meet the demands of modern employers.

Parents, too, are concerned about the financial and emotional toll this policy could take on their families. The additional years of waiting before their children can proceed to tertiary education mean more years of financial support, with no guarantee that their children will remain motivated to pursue their studies after such a long hiatus. The anxiety and uncertainty surrounding their children’s future could lead to increased stress within families, as parents struggle to navigate the implications of this policy on their children’s educational and professional prospects. This prolonged dependency could also strain family finances, particularly in a country where many families already face economic challenges. The added burden of keeping their children engaged and motivated during this waiting period could also lead to increased costs, as parents might feel compelled to invest in extracurricular activities or additional tutoring to ensure their children do not fall behind.

In addition, the new policy could exacerbate existing inequalities within the Nigerian education system. Students from more affluent backgrounds may be able to afford private tutoring or alternative educational opportunities during the waiting period, while students from less privileged backgrounds may not have the same options. This could lead to a widening gap between those who can afford to navigate the challenges posed by the policy and those who cannot, further entrenching social and economic disparities in the country. The policy, therefore, risks deepening the divide between the rich and the poor, as wealthier students may have access to resources that keep them academically and professionally competitive, while their less affluent peers fall behind due to circumstances beyond their control.