By Chidi Anselm Odinkalu

“THE judiciary has immense power. In the nature of things, judges cannot be democratically accountable for their decisions. It therefore matters very much that their role should be regarded as legitimate by the public at large” — Jonathan Sumption, Law in a Time of Crisis, 121 (2021).

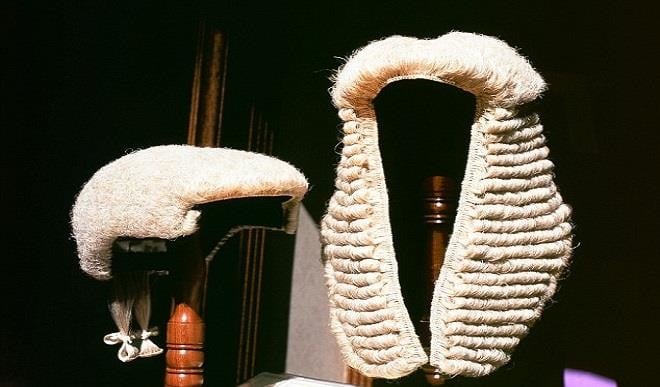

For a cumulative period of 17 years between 1885 and 1905, Hardinge Giffard – who was better known as Lord Halsbury – served three tenures as Lord Chancellor. In this capacity, he earned a reputation for having “appointed many undistinguished men to the bench because of their political services to the Conservative Party.” In 1897, Lord Salisbury, one of the prime ministers under whom Lord Halsbury served, advised him that “the judicial salad requires both legal oil and political vinegar; but disastrous effects will follow if due proportion is not observed.” For having so manifestly got the proportions out of kilter, Nigeria could be on course for a date Lord Salisbury’s predicted effects.

Abuja, Nigeria’s federal capital, is a place where mutual intercourse between lawyers, politicians and judges is both natural and habitual. It is home to judges too numerous to count and host to the headquarters of many court systems, including the High Court of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT High Court) as well as of Nigeria’s Court of Appeal and Supreme Court. The headquarters of the Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS Court of Justice) is also in Abuja.

The pace of production and reproduction in the courts in Abuja has been rather dizzying recently. On the penultimate day of the past working week, Nigeria’s supreme court in a case instituted by the federal government against the states issued a decision designed to make it mandatory for local government to be run only by elected officials.

This judgment has unlocked a predictable scrum of both political ululation and lamentation but the risk remains that its full benefits are likely to be undermined by the well-established jurisprudence of the supreme court in favour of bandit ballots which support the production of leaders at all levels who lack electoral legitimacy.

The day before the supreme court judgment, on the approach to the fourth anniversary of Nigeria’s #EndSARs uprising of 2020, the ECOWAS Court of Justice ruled that the conduct of the Nigerian government and its security agencies in their response to the #EndSARS uprising violated the guarantees of “security of person, prohibition of torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and association, duty to investigate human rights violations, and right to effective remedy.” In effect, the court said that the Nigerian government engaged in a cover-up of the violations that occurred during the #EndSARS protests, especially at the Lekki Tollgate in Lagos.

Weighty as they were, both of these otherwise seminal outcomes were relative non-events in the political and judicial registers of Abuja this past week. On the same day that the ECOWAS court delivered its judgment in the #EndSARS case to a near-empty gallery and the day before the supreme court held forth on the destination of local government funds, all roads led to the supreme court where the outgoing chief justice of Nigeria, Olukayode Ariwoola, presided over the inauguration of 22 new justices of the court of appeal and 12 new judges of the FCT high court.

Many people may have missed the number of justices of appeal inaugurated, however. Anyone who followed the reportage would have been forgiven for supposing that there were just two justices of appeal sworn in: “Wike’s wife and 21 others”, a reference to the wife of a political bruiser and current minister of the federal capital territory, Nyesom Wike. Also among the new justices of appeal is Abdullahi Liman, Kano’s self-appointed federal king-maker. The excess political vinegar in some of these most recent elevations to the court of appeal sadly detracts from the tasteful salad among others. For the sake of their own professional and career advancement in a cynical system, it is best at this time to preserve the anonymity of those deserving ones.

Among the 12 new judges of the FCT high court, at least seven were family members of serving or living judicial figures and three were family members of persons directly involved in the appointment process. Among these, the chief justice of Nigeria, who presided over the appointment, had his daughter-in-law made a judge; the chief judge of the FCT high court made his daughter a judge; and the president of the court of appeal got her daughter appointed a high court judge for the second time in three years. In 2021, Governor Simon Lalong of Plateau state made the same daughter a judge of the Plateau State High Court.

Responding to these appointments, Access to Justice, a group that monitors judicial independence and accountability in Nigeria pointedly said that “three candidates were ineligible to be considered for such appointments in the first place at the time the vacancies were announced.” This was about the daughter of the Chief Judge of the FCT High Court; the daughter of the President of the Court of Appeal; and the daughter-in-law of the outgoing Chief Justice of Nigeria. According to the group, these three appointments were a composite transaction between the CJN, the president of the Court of Appeal and the chief judge of the FCT High Court best described in local parlance as: “You scratch my back, I scratch your back.”

To say that these three appointments violate the judicial code of conduct as well as the regulations governing judicial appointments is to be kind to the lack of scruples at the helm of the current judicial appointment process in the country. It makes a joke of the judicial appointment process that someone in Nigeria can be appointed a High Court judge while holding a subsisting appointment as a High Court Judge.

In the days when the Nigerian judiciary was under credible leadership, these judicial inaugurations would pass almost as a non-event, attended only by select staff of the affected courts and by some members of the families of the new appointees. Reflecting the mood and mores of the times and consistent with the current tyranny of perverse incentives in judicial appointments, however, this swearing-in was a carnival taken over by cavalcades of dubious politicians and insider dealers in perverse political influence. Following the formal swearing-in of the new judges, Abuja was littered with “receptions” convoked by politicians and senior lawyers for many of the new judges.

There was good reason for the politicians to make an obligation of their noisy presence at the swearing-in of the new judges. Section 14(2) of Nigeria’s constitution loudly proclaims that “sovereignty belongs to the people of Nigeria” but under the colour of “rule of law” and judicial independence, the judges have toppled the people and installed themselves as the ones who alone can elect politicians to positions of power and influence in Nigeria. Access to political office now, therefore, is a transaction that begins and rests with political access to judges. Having thus murdered the rule of law, what we now have is a rule by judges under which both political power and judicial office have become bereft of legitimacy. The victim is the public good.

The week ended with a report which said that “[J]udges top [the] list of bribe recipients in Nigeria.” 15 years ago, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights warned that “the courts need the trust of the people in order to maintain their authority and legitimacy. The credibility of the courts must not be weakened by the perception that courts can be influenced by any external pressure.” In Nigeria, this is now a vain hope.