THE N3.52 trillion allocations to education in Nigeria’s 2025 budget has stirred fresh debate over the nation’s chronic underfunding of a sector crucial to its development. While this allocation represents a 61.47 per cent increase from the previous year’s budget and is the highest in the country’s history, it remains inadequate. At 7.07 per cent of the national budget, it is far below UNESCO’s recommendation that countries allocate 15 to 20 per cent of public expenditure or 4 to 6 per cent of GDP to education.

The history of Nigeria’s education funding reveals a consistent pattern of neglect. The sector’s highest allocation—11.12 per cent—was recorded in 1999. Since then, allocations have fluctuated, averaging a meagre 5.94 per cent in subsequent years. Recent allocations fell to 5.4 per cent in 2022 before recovering slightly to 7.9 per cent in 2024. These figures are dwarfed by the commitments of other African nations such as Namibia, which allocated 24.71 per cent to education in 2022 and 27.3 per cent in 2023, and South Africa, with 19.75 per cent in 2022. Algeria, too, has consistently recorded double-digit allocations for nearly a decade.

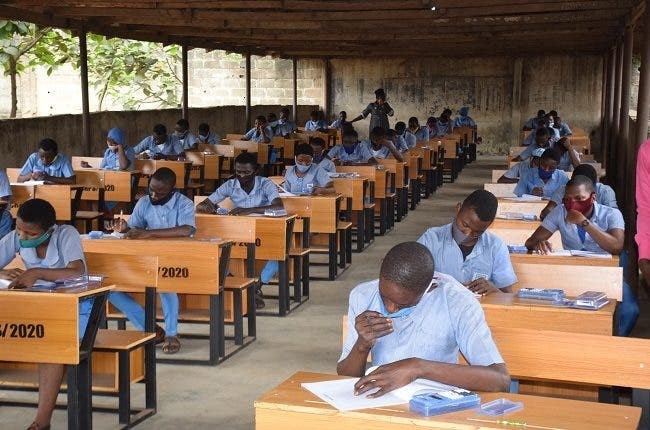

The consequences of this neglect are evident across Nigeria. The country has over 18.3 million out-of-school children—the highest globally. Inadequate funding has led to poor infrastructure, insufficient teacher training, lack of technology integration, and limited access for marginalised groups. These challenges have perpetuated declining academic standards, leaving Nigeria’s youth ill-equipped to compete on a global scale.

Experts have long emphasised the importance of increasing education spending to at least 20 per cent of the national budget. This level of investment is critical to addressing the sector’s challenges and unlocking its potential to drive long-term economic growth. Education is a key driver of development, with the potential to reduce poverty, foster innovation, and promote social cohesion. For Nigeria, prioritising education is not just a policy imperative; it is a necessity for national survival.

While the government made some significant strides, addressing the issues requires more than just increased funding. It must adopt a strategic approach to ensure that resources are effectively utilised. Budgetary increases should come with clear deliverables aimed at improving infrastructure, raising academic standards, and ensuring equitable access to education. Systemic issues such as corruption, which often diverts funds away from their intended purposes, must be tackled decisively.

Teacher welfare and professional development are also critical. The poor remuneration and working conditions in the sector have driven many skilled educators abroad, exacerbating the brain drain and overburdening those who remain. To reverse this trend, the government must prioritise competitive salaries, continuous training, and improved working environments for teachers.

Infrastructure development is another pressing need. Many schools in Nigeria lack basic facilities such as classrooms, libraries, and laboratories, particularly in rural areas. Without significant investment in this area, efforts to improve educational outcomes will be futile. Equally important is the integration of technology into the education system. Providing schools with modern tools and training students in digital skills will better prepare Nigeria’s youth for the demands of the global economy.

The underlying social and economic factors driving the out-of-school children crisis must also be addressed. Poverty, insecurity, and cultural barriers continue to deny millions of children access to education. A holistic approach that combines increased funding with targeted interventions is essential to tackle these challenges and ensure that every child has the opportunity to learn.

As Africa’s largest economy, Nigeria cannot afford to fall behind its peers in prioritising education. The government must act decisively, recognising that the future of the nation depends on the quality of education it provides today.