SHORTAGE of teachers is one of the biggest issues facing the education sector in Nigeria. Though this problem has always existed, it has taken on a broader dimension in recent years. A combination of this issue and other factors continues to hinder the progressive course of education at present. The shortage affects all three levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary.

Recently, the Teachers Registration Council of Nigeria (TRCN) even raised an alarm over the issue, lamenting that it has reduced the number of teachers available to impart knowledge. The Council’s Acting Registrar/Chief Executive Officer, Stella-Maria Nwokecha, reportedly said that this ongoing problem would dominate discussions at the forthcoming fourth online meeting of registered teachers in Nigeria. A good step, no doubt.

Instances of this shortage are widely known across the country. The news media are filled with reports of such shortages, to the extent that their sheer scale often confounds both the public and policymakers. Sometime in 2022 or thereabouts, a primary school in one of the northern states was reported as not having a single teacher for any of its classes, leaving the pupils to play throughout the school hours.

Similarly, a comparable scenario was reported in the online media, indicating that Okugbe Primary School, Ikpide-Irri, Isoko South Local Government Area of Delta State, had only one teacher handling all the classes, with a total of 170 pupils. The embarrassing situation prompted an immediate promise by the Chairman of the local government council, Mr. Friday Ovoke Warri, to address the issue as a matter of priority.

There are many schools with only one or two teachers in various states across the federation. Most remain undiscovered, either due to their remote location or because the media have not been alerted to these areas. These schools exist even in the southern part of the country, which enjoys greater respect than its northern counterpart, owing to the south’s substantial investment in education over the years.

The persistent shortage has led some well-off citizens to hire teachers, whom they pay from their own pockets, either monthly or quarterly. This positive development, which reflects a commendable form of collaboration between citizens and the government, has rescued many schools that had been suffering from a lack of teachers.

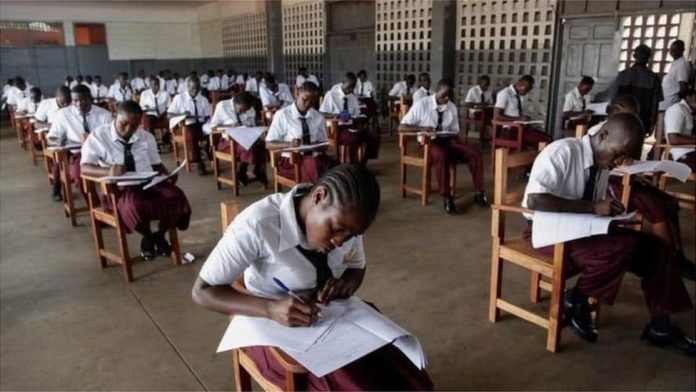

While the shortage affects all three levels of education, it is most pronounced at the primary level, which is so crucial to the educational development of individuals as a foundational, formative stage. It is difficult to imagine the reality of a school with only one teacher.

The heavy workload prevents the teacher from providing the level of knowledge needed by pupils as they advance from one class to the next. In the end, it is the children who suffer, which in turn impairs their developmental prospects.

We believe that the situation has worsened due to poor budgetary allocation to the education sector. Yes, on a broad scale, education has attracted meagre funding from both the federal and subnational governments, but the situation is even worse at the local government level. This tier of governance must do more to improve the fortunes of primary schools, as primary education is primarily under its jurisdiction.

As dire as the situation may seem, it is not beyond remedy if the government prioritises the funding of primary education. One way to achieve this is by increasing budgetary allocations in the next fiscal year. Allocating more than the paltry amounts currently given to the sector is essential. In the 2023 and 2024 budgets, 7.9 per cent and 6.39 per cent, respectively, were allocated, significantly below the benchmark recommended by UNESCO.

We also advocate for periodic intervention by both the federal and state governments in primary education. The Delta State Governor, Rt. Hon. Sheriff Oborevwori, commendably approved the recruitment of over 3,000 teachers and other staff for primary schools, which has gone some way towards addressing the shortage of teachers in the state.

Our considered opinion is that leaving primary education solely to the last tier of governance may not bode well for the desired development of education. Like the base of a pyramid, primary education forms the foundation for all subsequent educational pursuits and must be supported to produce quality pupils who will move on to secondary education. Let all tiers of governance work together for the good of society.